Sterile Working Practice

Sterile working practices are important for all mushroom growers, whatever their level or scale. Growing mushrooms at home is an enjoyable and very rewarding pursuit but it needs growers to develop and maintain good sterile working practices. Anything less and it can lead to tears.

Sterile working practices are important for all mushroom growers, whatever their level or scale. Growing mushrooms at home is an enjoyable and very rewarding pursuit but it needs growers to develop and maintain good sterile working practices. Anything less and it can lead to tears.

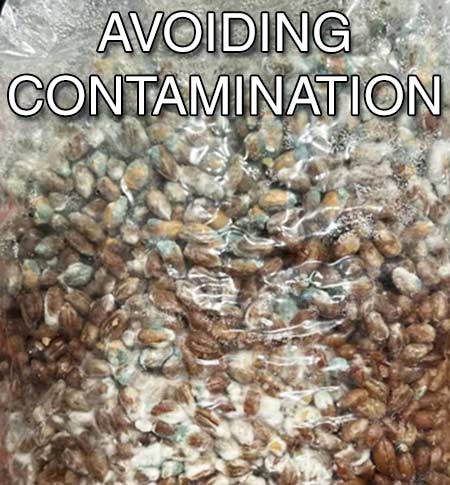

When you hear people talk about ‘contamination’ in relation to mushroom growing they’re generally talking about spores and bacteria that inadvertantly join the party. When this happens the end result of this is often a ruined grow, blighted by unwanted mould or decay. Unwanted spores can be found floating in the air around you, which means they’ll also have fallen on your clothes, in your hair and on every possible surface. The same applies to bacteria, though the majority will be found on your skin and in your breath. That’s nothing personal – it’s just how it is.

The good news is that with a little care, you can hugely reduce your chances of getting contaminated spawn or substrates.

Sterile Working at Home

The average home mushroom grower can’t follow the sterile working practices employed by commercial growers; quite simply, they’re either too expensive or take up too much space and equipment. That said, a little time and effort can compensate for a lot of that.

Supplies

Firstly, you need some basic supplies. Your new best friends will be a (very) good supply of 70% Isopropyl alcohol with refillable spray bottles for application, alcohol wipes, decent quality paper towels, bleach and a heat flame source – a bunsen burner/small butane burner or similar. On top of that, you’ll want a supply of disposable nitrile gloves (long-sleeved medical ones are best if possible). Oh, plus that supply of unused (medical grade) covid facemasks you still have lurking somewhere in the house!

Firstly, you need some basic supplies. Your new best friends will be a (very) good supply of 70% Isopropyl alcohol with refillable spray bottles for application, alcohol wipes, decent quality paper towels, bleach and a heat flame source – a bunsen burner/small butane burner or similar. On top of that, you’ll want a supply of disposable nitrile gloves (long-sleeved medical ones are best if possible). Oh, plus that supply of unused (medical grade) covid facemasks you still have lurking somewhere in the house!

For work like inoculating grain/grow bags or work with spores, liquid culture or agar and also grain transfers (bag to bag or bag to jar) a “still air box” is invaluable. If you’re loaded, a HEPA14 laminar flow hood is even better than a still air box, but only if it’s large enough and decent quality. In our opinion, many of the cheap and small flow hoods coming into the UK from China are not really up to the job.

Workspace

The problem with growing mushrooms at home is that we have families, often children, and they all need space. Somewhere to leave their half-eaten sandwiches dirty clothes and the dog’s collar. None of those things are helpful! If it’s at all possible you’ll want to requisition a room which is reserved for mushroom use only, with a door that can be kept closed at all times. Somewhere you can turn into your sterile workspace. A couple of tables, cupboards and chests of drawers will always be useful.

Your aim is to keep the air in that room as undisturbed as possible, keep unwashed hands out and keep all surfaces spotlessly clean. All those things are possible (even if a little bribery is required with children).

Initial clean

First things first, if your spare room needs a hoover, get it out of the way a couple of hours before trying to clean surfaces. Hoover and let the air and dust settle first. Once that’s done and, armed with your cleaning supplies, clean every possible surface. Wipe all surfaces down with dilluted bleach first, then dry them. Next, clean those surfaces again using your 70% alcohol to remove any traces of bleach and kill anything the bleach didn’t finish off. This isn’t a 100% effective way of creating a sterile working space, but it’s as close as anyone outside a pharmaceutical lab can get. Disinfecting this way needs to be done every time you need to do any ‘clean’ work relating to mushrooms.

Personal Cleanliness

Your hands, skin, clothes, hair and breath need attention next. Dead skin cells, loose hairs and general dust are falling off your clothes and body all day, every day. These are not welcome visitors at the mushroom party. The full obsessive approach is to wash your hair, change into clean clothes, put on a facemask, put on disposable gloves and clean them with alcohol before and after touching anything. Longer gloves are better as they protect against anything falling off your arms.

Sterile equipment and tools

Everything you use and touch needs to be sterile. Again, alcohol is your friend here. Clean everything, including the outside of any bags (grow bags, grain bags and so on) with alcohol and wipe dry with a clean paper towel. Do the same with injection ports, if you’re using that sort of bag. Wherever possible, avoid touching bag air filters – they will filter air for contaminants but are way less effective at protecting against touch contamination.

Everything you use and touch needs to be sterile. Again, alcohol is your friend here. Clean everything, including the outside of any bags (grow bags, grain bags and so on) with alcohol and wipe dry with a clean paper towel. Do the same with injection ports, if you’re using that sort of bag. Wherever possible, avoid touching bag air filters – they will filter air for contaminants but are way less effective at protecting against touch contamination.

With syringes, for example liquid culture or spore syringes, the needle must be totally sterile. If the needle is still in its sealed wrapper, it should already be sterile. Items such as scalpel blades and previously used needles are quickly and easily sterilised using nothing more than a simple heat source – something like a little butane burner, bunsen burner or alcohol lamp. The item is placed in the flame and heated until red hot and you can then clean and cool it prior to use by using an alcohol wipe.

Containers

If you’re transferring things from one container to another – for example adding colonised grain spawn with substrate in a tub, splitting grain from a bag into multiple jars (or similar) or performing grain to grain transfers in other ways, it is massively important to ensure the source containers and also the destination containers are spotlessly sterile. How you manage this depends on the container type and material.

Glass containers/Jars

Anything made of glass should ideally be sterilised in an autoclave (you won’t have one) or pressure cooker (needs to run at 15psi, which most in UK don’t). Truth be told though, even if you sterilised using one of these devices at home, the containers would be taken out of the steriliser and straight into air that isn’t sterile (unless the air in your house runs through HEPA filters!). That being so, dilluted bleach, followed by boiling water, followed by a good clean with alcohol once they are in your workspace is about as close as you will get to sterile. The same applies to containers made of other materials.

Note: it is important to ensure your containers are also fully dry before use. Leaving drips of water inside them is an invitation for the contamination circus to start performing their tricks.

Some items can be sterilised fairly well in your oven. Glass petri dishes and glass containers (without rubber/silicone lids), metal tools can be wrapped in layers of kitchen aluminium foil, ‘baked’ at at least 120 degrees celcius and then kept in the foil wrappers until ready for use. However, allow the items to cool before trying to move them – as they, outside (non-sterile) air will be sucked into the foil wrapping. Sterilising plastic items in the oven is not the best of ideas unless you like the strange shapes molten plastic can create!